Nicholas Hilliard was England’s first English artist to become internationally famous. His self portrait (© Victoria & Albert Museum, London) is a mere 41mm in diameter (1.6 inches) and it is for these exquisitely delicate and miniature images of Elizabeth I and her court that he becomes famous.

I fell in love with Hilliard’s miniatures portraits when I was a teenager and harboured ambitions to become an artist. His tiny images had details that hinted at an expertise to which I could only aspire. At the age of thirteen I did have a painting exhibited in London’s National Gallery’s Children’s Summer exhibition, but that was more years ago than I care to remember. It was not until I did my Master’s degree in medieval and early modern studies at the University of Kent that I was able to study Hilliard in greater depth, as well as the times in which he lived and the influences he absorbed from and through his teacher, Levina Teerlinc. Over the years, part of my research has been into the symbols and emblems used in medieval and early modern illuminated manuscripts and although Hilliard was painting for a mainly Protestant audience, many of these symbols appear in some of his paintings.

We know Hilliard was born in Exeter, but the year is still debated as the parish records have been lost. Generally the year 1547 is accepted, but there are still some dissenters.

The oldest son of a goldsmith, Richard Hilliard and his wife Laurence, both Nicholas and his younger brother John would both follow in the footsteps of their father and become goldsmiths. It would be Nicholas who would go on to be remembered down the centuries, but not for his goldsmith’s work. Nicholas went on to become the favoured artist of Elizabeth I, creating tiny portraits of the Virgin Queen who gave these small images of herself to loyal courtiers, diplomats and perhaps as love tokens to the love of her life, Robert Dudley. These tiny portraits are what made Hilliard famous both in England and internationally. Not only did he paint these small portraits, he also painted larger ‘table’ portraits of the queen. Recently another portrait of the Virgin Queen, together with one of Sir Amyas Paulet, have been discovered.

Hilliard was brought up a Protestant and as a child spent time in exile in Geneva with the family of John Bodley, who was also a prominent citizen of Exeter. Richard Hilliard had decided to send his eight year old son away with the Bodley’s in 1555 during the reign of Henry VIII’s Catholic daughter, Mary. As those fascinated by Tudor history know, to be a Protestant during Mary’s reign was to court persecution and death. Many adherents to the new Anglican church fled to Protestant Europe and found their way to Geneva where the reformist theologian, John Calvin, was living and preaching. It is very likely the Hilliard was educated with the Bodley children. John Bodley’s son Thomas went on to reform the Oxford university library that now bears his name, The Bodleian.

Hilliard painted this miniature portrait of Thomas in 1598 , the same year that the new library became operational, and coincidentally the same year Hilliard drafted a treatise of how to paint and prepare pigments. Hilliard possibly started this project at the request of his childhod companion. The draft treatise contains many similarities to another treatise published in 1573 by Anon, but includes Hilliard’s anecdotes of when he painted the Virgin Queen, his ideas of the rank of the person suitable to paint these portraits, as well technical details on how to prepare and mix pigments.

During the reign of Mary I, there were several other English families living in Geneva including that of Francis Knollys (1511-1596). Francis was married to Catherine (née Carey) (c1524-1569) the daughter of Mary Boleyn and William Carey and therefore cousin to the future Elizabeth I. Frances and Catherine had fourteen children, one of whom was Letitia who was first married to Walter Devereux in 1560, and much later in 1578, married the queen’s favourite, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. Much has been written about Dudley’s reasons for marrying Letitia, but the marriage resulted in them both being banished from court. Dudley was eventually allowed to return, but Letitia was never allowed to see her cousin, the queen, again. One of Hilliard’s portraits of an Unknown Lady is thought to be of Letitia and while some might accuse me of fantasy, it would be logical that Hilliard would be asked to paint her at the time of her wedding in 1578. Robert Dudley had been a very loyal patron so it is very likely he would have commissioned a portrait of his new wife from his favourite artist.

What has long been debated is Dudley’s relationship with Elizabeth. Some years ago two miniature Hilliard portraits of Elizabeth and Dudley were put up for sale in 2009 fetching £80,000. They are clearly a pair and are only 15mm high (that is just over half an inch). Their size suggests were probably painted for inclusion in a ring, but the ring no longer exists. Some might consider this thought speculative, but perhaps Hilliard also created the ring they once sat in.

But I digress. The records of the Goldsmiths’ Company reveal that in 1562 Nicholas Hilliard was apprenticed to the queen’s goldsmith, Robert Brandon, and became a master goldsmith in 1569. This is evidence of his official training as a master goldsmith, but the greater question for us is who taught Hilliard the art of limning? In his draft Treatise of of 1598 Hilliard tells us that his inspiration was Hans Holbein the Younger, but this inspiration could only have come from examing paintings or sketches because Holbein had died in November 1543 – some four years before Hilliard’s birth. The Royal Collection contains many sketches of members of the court of Henry VIII, and it is very likely that Hilliard would have seen these as well as the original great mural of Henry VIII, his father, mother and Queen Jane painted by Holbein on the walls of the private royal apartments in Whitehall Palace.

Logically Hilliard must have had draughting skills in order to design items to make as a goldsmith. What we do not know is whether he learnt to handle watercolour on vellum before becoming apprenticed to the queen’s goldsmith, Robert Brandon, or after. I know what I was capable of producing artistically as a teenager, so it is very likely that he learnt these techniques prior to joining Brandon’s household, but from whom?

The artist who had been appointed to replace the court limner Lucas Horenbout who had died in March 1544, was Levina Teerlinc. Teerlinc was still at court in the 1560s therefore logically, it is she who is the most likely candidate to be his teacher. Levina Teerlinc was the daughter of the last of the great Flemish illuminators, Simon Bening. Levina had married George Teerlinc of Blackenberg in 1545, not long before it is thought she and her merchant husband came to London. The first time she appears in the king’s accounts is in 1546 where she is granted an annuity of 40l per annum, to be paid quarterly in arrears ‘at the king’s pleasure’. It was a greater annual sum than received by Horenbout and was paid ‘unto her husband, George’. In the royal accounts the spelling of the Teerlinc varies through Terling, Tarling, Teerling and Tarlinc in the various entries over the years. After Queen Mary dies, there are a couple of interesting entries in these accounts. Robert Brandon is listed as being paid £1500, and Teerlinc’s name appears immediately underneath his and she is paid £150. Coincidentally, this is the total amount of the annuity that was outstanding from the beginning of Mary’s reign to the quarter before the queen’s death in November 1558. There had been no further patent since Teerlinc was first employed by Henry VIII ‘at the king’s pleasure’, but payments continued under Edward VI. My examination of the accounts revealed that payments had ceased under Mary.

In November 1559 Teerlinc was granted a lifetime annuity by Elizabeth I in recognition of her loyalty to the Tudor family. Despite painting the first of many portraits of Elizabeth I in 1572, Hilliard would have to wait until much later in his career to receive a similar annuity and that would be well after Teerlinc’s death in 1576.

There is another one of Hilliard’s Unknown Ladies dated 1572 in the Buccleugh collection, which tells us she is aged fifty two. 1572 is also the year that Hilliard first paints the queen so it is possible that this portrait was Teerlinc’s way of introducing her young protégé to the queen, thus giving Elizabeth I a new artist who was capable of taking on the task of official limner. The queen was apparently not keen on being reminded that she was ageing, so this would be a masterly way of introducing someone who was talented, and since Teerlinc had known the queen ever since she was a teenager, she would have been well aware of Elizabeth’s predilection for a handsome face. Trained by her father, the last of the great Flemish illuminators, Teerlinc was well versed in the visual language of symbols and emblems used in illuminated manuscripts and would have schooled her young pupil in such a way that he could adopt these for an English client base. Levina Teerlinc died the month before Hilliard’s marriage in July 1576 to Alice, the daughter of the man who taught him goldsmithing, Robert Brandon.

There is a printed treatise, written by someone very well versed in the art of illumination, that was first published in 1573, that describes the art of a limner giving recipes and instructions for the preparation of surfaces, colours and various ways to apply these and gold and silver leaf. It is possible that it was written by Teerlinc and the absence of her name is in keeping with the position of women in society at that time. Women were not supposed to have an opinion, let alone a career, therefore the publisher, Richard Tothill, who was also a cartographer may well have done so on the proviso that her name did not appear. Hilliard’s later draft treatise of 1598 replicates much of this earlier book including how to create faux jewels using coloured resin applied over silver leaf.

The Virgin Queen’s favourite, Robert Dudley, knew of Hilliard’s work long before our artist came to the notice of the Elizabeth I and since Teerlinc had been at court since 1546, it is possible Dudley was introduced to her protégé through her. Hilliard first painted Elizabeth in 1572. This miniature is in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

1573 was the year when it is now thought Hilliard painted a large portrait of Elizabeth known as The Phoenix portrait also in the National Portrait Gallery, London. Comparing this portrait with the tiny one only 15mm high sold in 2009, it becomes apparent that there are many similarities, suggesting they may have been painted in the same year. Certainly it is very apparent even to those who are not art historians that this face becomes a template for future portraits.

The Pelican portrait probably followed the next year and research has revealed that it is the same as the Phoenix except it has been flipped. While undergoing conservation, X-ray analysis of the Phoenix revealed Hilliard had moved the position of the eye. This is clear evidence that the artist was working through his ideas and underdrawing of this sort is called pentimenti. There is no such change of mind in the Pelican which is why it is concluded that this portrait was the second. Clearly painted to hang together, facing each other, it is clear statement of Elizabeth’s desire to be single as she is portrayed in the traditional place for both a husband in the Phoenix, and a wife as in the Pelican.

The National Portrait Gallery, London, attributes these two portraits to Hilliard’s brush.

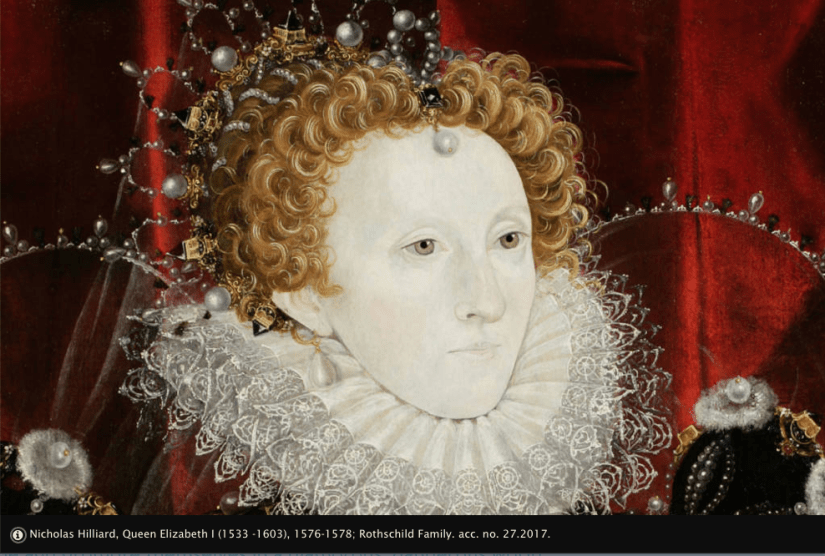

In 2018 Dr Carey, senior curator of the Rothschild collection at Waddesdon Manor, revealed two more portraits by Hilliard that had been in the collection and lain unrecognised until recently. One being of the queen, and this is a screen shot from the Waddesdon Manor website (a fabulous place to visit)

and the other being of Sir Amayas Paulet. Sir Amyas is wearing a locket and this may well have contained a miniature portrait of the queen painted by Hilliard.

It is impossible to over state the importance of these finds as they give scholars of Hilliard another pair of portraits to pour over and analyse. Through scientific analysis of pigments and examination of the dendrochronology, their work will add to the slowly building database of Hilliard’s methods and hopefully eventually we will be able to identify more of his sitters. When Dr Carey presented her paper on the two Hilliard portraits at a conference held at the Royal Maritime Museum, Greenwich earlier this year it was immediately apparent that the queen’s face was created from the same template as the Phoenix and Pelican portraits.

By the mid 1570s Hilliard had become firmly established at court as Teerlinc’s successor. Shortly after their wedding in July 1576, the newly weds left for Paris as an unofficial part of the new ambassador’s entourage. That ambassador was Sir Amyas Paulet. Hilliard’s wife Alice returned to London in 1578 because she was pregnant. The portrait of Alice Hilliard dated 1577 the symbols such as the ear of corn and the pink rosebud pinned to her bodice are a subtle way of telling us she is pregnant .

Hilliard painted a portrait of his father in the same year and since the younger Hilliards had gone to Paris in 1576, it is assumed that Nicholas painted this portrait of his father Richard during his father’s visit to France. It is not beyond the bounds of possibility that Alice was chaperoned by her fifty eight year old father-in-law on her return trip to England.

1577 is the year Hilliard painted his self-portrait. He was aged 30.

Look closely and you will see there is a sprig of dandelion tucked into his hat band. The dandelion is one of the medieval floral symbols of grief. Perhaps he gave this portrait to Alice as a token of his love and how he was grief struck at the thought of their separation when she was to return to London with his father.

Since France was a hot spot for Protestants (it was only six years since the St Bartholomew’s Day massacre), another layer of meaning might be that this sprig of dandelion refers to Hilliard’s remaining in the French lion’s den of religious upheaval. The French for dandelion is ‘les dentes de lions’, which refers to the shape of the leaf considered to resemble the teeth of a lion. This may well be the reason why they called their first born Daniel after the Old Testament Jewish hero who, when thrown into arena to be torn by lions. Daniel survives because the lion recognises him and does not tear him limb from limb.

We know a little about the life the Hilliard’s led in France, but from surviving portraits we know he painted of the members of the French court, such as the portrait of the Duc d’Alençon. Hilliard has omitted the terrible small pox scars that marred the Duke’s face.

We know a little about the life the Hilliard’s led in France, but from surviving portraits we know he painted of the members of the French court, such as the portrait of the Duc d’Alençon. Hilliard has omitted the terrible small pox scars that marred the Duke’s face.

On his return to England in 1578 Hilliard’s career blossoms. It may be this year that he was sent to paint the woman who was at that time, a ‘guest’ of George Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury. It might seem odd for a modern audience but there was probably a season for painting miniatures. Consider how in an English winter our natural light is limited both in day length and in lux levels. It seems logical that the late summer 1578 was a possible date for our artist to travel to the Earl of Shrewsbury’s seat and paint the Earl’s royal guest when the light and day length were still good enough to paint by. However, it is also possible that he was sent up to Tutbury prior to 1576.

Hilliard painted two miniature portraits of Mary, and in this one in the Royal Collection Hilliard has used the expensive blue pigment made from ground lapis lazuli for the intense blue background. The other portrait, with the lesser blue pigment made from azurite, is now in the Victoria & Albert. This latter portrait was known to be in the Royal Collection during the reign of the Stuarts and when James II fled to France in 1688 he took it with him. At some point in the past it was suggested that these were painted by Hilliard in 1560. Despite Hilliard having a phenomenal talent, it is highly unlikely that anyone would commission a thirteen year old boy to paint a queen.

In his draft treatise, in addition to giving us an insight into when it was the best time of year for painting, Hilliard tells us that the sulphur from the fires from coal fires and the fumes from gold-smithing will affect certain pigments, which suggests he kept his gold-smithing separate from his painting. This provides another clue that he painted in the summer when there were fewer domestic fires. There is evidence for this dating from the 19th century when the National Portrait Gallery was given the 1572 portrait miniature of Elizabeth. The miniature had been in the collection of the Earl of Jersey, and the air in the Channel Islands (the ones in the English Channel for my American readers) is very pure. When exposed to the London atmosphere, albeit indoors and certainly very carefully looked after by the NPG, the white pigments started to turn yellow. This was because of the amount of sulphur in the London air and caused much alarm. Thankfully, the yellowing was reversed and the white areas are white.

The Hilliards had seven children in all. Hilliard’s son Daniel was born in the May if 1578 while his father is still in France. Daniel was their firstborn. It has been speculated that their daughter Elizabeth was named after the queen, which seems logical, but it is unknown if the queen was the child’s godmother. Their son Francis may have been named after Sir Francis Knollys, but since Hilliard painted a miniature of Sir Francis Drake the child may have also been named in honour of the great naval captain.

Lawrence, named after his grandmother, would go on to follow in his father’s footsteps, but did not have the same level of talent. Was Lettice named after Letitia Knollys? As you see, the naming of the Hiliard brood was certainly linked with those at court, but we do not know precisely which courtier might have been godparent. Sadly there was a still born son who arrived on Christmas Eve 1584 who was named after his father.

Their last child was a daughter named Penelope. Homer’s Penelope (the faithful wife of Odysseus) is often considered to be the embodiment of marital fidelity, and since she was the last of the Hilliard’s children, perhaps she was named as a statement of the faithfulness of Alice and Nicholas to each other.

In my novel The Truth of the Line I have said the Hilliard’s last child is named after the wife of Marcus Teerlinc. Marcus was the son of Levina and George Teerlinc and followed in his father’s footsteps. I have him living longer than he actually did, and married to a woman called Penelope, but whether or not his wife was actually called Penelope is unknown. Since Marcus was a merchant, I thought it apt for his wife’s name to reflect his ocean exploits, which may or may not have been similar to those of Odysseus. A portrait of an Unknown Lady, now in the Victoria & Albert Museum, was first thought to be that of the Levina Teerlinc, because of the identification of the tiny die that nestles in her ruff as a toy that in Dutch is called a ‘teerling’, which is another way of spelling Levina’s married name, as seen in the royal accounts. However, since the age of the sitter is revealed as being fifty and those who study fashion have identified this woman’s clothes as being of the styles worn at the end of the 16th century, this woman was alive long after Levina had died, but perhaps it is the widow of Marcus Teerlinc. It is possible there is another Hilliard miniature in the locket that hangs over this woman’s heart.

Another example of the limners’ art is The Ashbourne Charter granting the people of Ashbourne a Free Grammar School, which was illuminated by Hilliard in 1585.

The charter for the founding of Emmanuel College, Cambridge has a nearly identical illuminated letter E at the beginning of its charter, and coincidently the college was founded in 1584 by Sir Walter Mildmay. Clearly our artist was so pleased with this design for the letter E that he chose to repeat it. The Ashbourne charter not only includes visual references to the Tudors, but a grey falcon, holding a sceptre and wearing the imperial crown appears on folio 3. When the bird was originally created it would have glittered in the light as it is of silver leaf which has oxidised and turned grey. Hilliard originally used silver leaf to denote the falcon being white, which anyone who knows their Tudor emblems will know this was the personal emblem of Elizabeth I’s mother, Anne Boleyn.

Other Tudor references in the margin of this charter are the Beaufort portcullis, the red and white Tudor rose en soleil, and red roses of Lancaster. It is well known that the queen’s mother wished for proceeds of the dissolution of the monasteries to be used for education, but for this overt rare visual reference to the queen’s mother to be placed above the words on the final folio suggests that there must have been a conversation about the inclusion of the Boleyn falcon. Perhaps this conversation was with the queen herself, or more likely it was with the man who commissioned Hilliard to illuminate this charter. It is clear that Anne Boleyn’s desire for education to be available to a wider element of society was well known – either by the patron, or by Hilliard himself.

The surviving account for the creation and decoration of this charter itemises the amounts paid for the preparation of this illuminated document paid by the rich Derbyshire merchant, Humphrey Strete, being a total £28 12s. There are two specific items of interest in the bill, the first being ‘for the ingrosinge of this patente’ being the preparation of the written elements, followed by an item ‘for the lymmninge & garnishinge of the same’. This latter item is specifically for the painting and decoration of the charter and from this we learn that Hilliard was paid some £4 16s 8d for his efforts (about £16,600 in today’s money).

1583 saw the queen reach the age of 50, a good age for anyone in the sixteenth century, but for a queen who was aware of the benefits of visual propaganda, there was no possibility of allowing a realistic representation to be continued to be created. Hilliard had to think up another way continuing the idea of the English’s monarchs status of the Virgin Queen. He came up with the idea of focusing on her fabulous wardrobe and jewels, with her face becoming a mask. As Roy Strong so rightly observed, Elizabeth portrayed as Gloriana was born.

Using symbols that continued to promote Elizabeth’s status as England’s Virgin Queen, Hilliard’s portraits become glittering images full of faux jewels created by dropping coloured resin on top of burnished silver leaf, with her features being less important. This is a restored Hilliard miniature of Elizabeth I that is in the Royal Collection.

The gossips stated that by the 1590s Hilliard was able to produce a recognisable image of the queen in a mere four lines. This particular portrait dates from then and is a great example of these portraits of Elizabeth that have become known collectively as The Mask of Youth. Sixteenth century artists would paint diamonds as black. However, on many portraits, especially if it is a black dot on a pearl, the black is more likely to be oxidised silver leaf. In the absence of detailed information on many of these images, this is speculation, but if it were to be silver leaf then the effect would have been a shimmering fantasy of Elizabeth’s jewels and fabulous dress, with her face being merely a repetition of an early template Hilliard had in a workbook. However, Hilliard had painted her image so many times he could probably have sketched her face in his sleep.

Look carefully at this portrait and you will see there is a jewelled crescent moon in her hair. Any educated Tudor person would recognise a crescent moomas being an emblem of the virgin goddess of the moon, Cynthea, also known as Artemis in Greek mythology, or Diana in Roman. A study of the classics was de rigeur for any child of Tudor nobility or the aspiring merchant classes. The contemporary viewer would immediately recognise this symbol as representing the queen’s virginity and that she is a divine being, as well as the long established meaning of the gemstones – diamonds for constancy, pearls for purity and rubies for love or sacrifice. When a Hilliard miniature of this type went under the hammer in 2007 it went for £276,000 being $560,000 at that time.

Unsurprisingly, considering how he was favoured by the queen, Hilliard also designed the second Great Seal of England that was used on official documents from 1586-1603; the first had been designed by his teacher Teerlinc. Heavy with symbols of power and her divine right to rule; inscribed ‘Elizabetha dei gracia Anglie Francie et Hibernie Regina Fidei Defensor’ (‘Elizabeth, by grace of God, Queen of England, France and Ireland, Defender of the Faith’) this image of the queen is very similar to illuminated letters appearing on both charters for the Ashbourne grammar school and Emmanuel College. Without the Great Seal being attached to any document carrying the monarch’s signature meant the written content of that document was not official. Evidently, when Elizabeth signed the death warrant of her cousin, Mary Queen of Scots she gave specific instructions that the Great Seal was not to be affixed until she said so. What happened next is history!

Hilliard was kept busy painting portraits of the queen, Robert Dudley and many others whose identities have long been lost. One of the most intriguing is one in the Victoria & Albert museum of an unknown young man with red hair who holds the hand of a woman emerging from a cloud.

Unlike many other Hilliard portraits that state the age of the sitter and the year the portrait was painted, this one merely states the year, 1588, together with the apparently nonsensical latin motto Attici Amoris Ergo. The motto translates as ‘by, with, from, or through the love of Atticus’. As we all know, 1588 is the year of the attempted invasion by the Spanish Armada. Whether this is the year this portrait was painted for a lover, or perhaps the year this young man died, we do not know. It has to be the most intriguing of alI Hilliard’s portraits. After sixteen years of research, I am now in the process of writing up my research into this miniature and believe I have unravelled the intent behind this motto, and will also propose an identification of the sitter.

Painted slightly later than the Attici Amoris Ergo portrait, Hilliard’s Young Man Among Roses is a full length image of a young man leaning against a tree.

Roy Strong has argued that this portrait is of the young Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, but not everyone agrees. Certainly this young man appears to be the epitome of a foppish youth who appears to be entwined by one of the queen’s emblems, the eglantine. He is dressed in black and white – the colours of the queen’s livery – and at the top there is another puzzling motto, Dat poenas laudate fides (My praised faith procures my pain). This has been identified as a quote from the Roman poet Lucan who wrote the poem, De Bello Civili. Clearly the quote is relevant to the sitter, or perhaps both sitter and the recipient of the image, but unfortunately we have no idea for whom this full length portrait was destined. Lucan’s poem is about Julius Cesaer’s war against Pompey the Great in 48-49 BC and known as Pharsalia, after the Battle of Pharsalus of 9th August 49 BC being the definitive battle in Julius Caesaer’s war against Pompey the Great and the Senate. Is this a portrait of a love lorn swain, dying of love because his heart is entwined within the eglantine rose?

Perhaps the warlike reference is to do with the heart’s battle in love, or maybe the meaning is a very specific one that was only understood by the recipient. Like the young man holding the anonymous woman’s hand coming from a cloud, the intent of this motto also remains a mystery. These references to ancient people and classical poetry demonstrates how Hilliard must have had a knowledge of their written works.

It could be considered a romantic notion to picture both Thomas Bodley and the younger Hilliard sweating over their latin grammars and translating the works of Cicero and Lucan, but in 1598 Hilliard is keen to state how the art of limning is only for gentleman. He qualifies this by telling us that the artist has to be able to converse with their sitters who, by implication, are educated. Since he also tells us that he has painted the queen ‘from life’ and we know she was a very educated woman, then it is another, slightly covert way, for Hilliard to brag about his exclusive client list.

Robert Devereux succeeded Robert Dudley as Elizabeth’s Master of Horse. Dudley was both his godfather and eventually his stepfather. In 1588 Devereux twenty two years old. Painted in the same year as the red haired young man with the unintelligible latin motto, Hilliard’s miniature tells us in his exquisite gold lettering that this young man is aged 22. The date of 1588 in these two miniatures made me wonder whether these two young men had their portraits painted because they were off to fight the Spanish and were leaving a portrait for their loved ones to remember them by in case they never returned. In more recent times many soliders going off to war had their photographs taken for just this purpose.

Isaac Oliver painted Robert Devereux in 1597 and this portrait of the 2nd Earl of Essex is now in the Royal Collection.

Hilliard lived and worked in Gutter Lane next to the Goldsmith’s Hall in a property he leased from the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths. In addition to his own commissions, he was teaching the art of limning and we know of two young men who benefited from Hilliard’s expertise. The Englishman Rowland Lockey was apprenticed to him as a goldsmith and Isaac Oliver learnt how to paint portrait miniatures. Oliver does not appear in the lists of apprentices in the records kept in the Goldsmith’s Hall, so we know he was not apprenticed to learn this discipline.

French born Isaac Oliver (c1565-1617) went on to become the favoured artist of James I. One of Oliver’s paintings of the 1590s is an allegorical image of Elizabeth I and is a re-working of this painting (below) attributed to Hans Eworth and held in the Royal Collection.

Eworth has reworked the story of the Judgement of Paris where the mortal, Paris, is asked to judge a beauty contest between the three goddesses, Venus, Juno and Minerva. Paris’s decision leads to the Trojan war. In Eworth’s painting, the artist has made a couple of substantial differences to the original story substituting the English queen for Paris, the golden apple becomes the orb, and instead of the queen awarding the golden trophy to one of the three goddesses, she keeps it for herself. The Eworth painting is still in its original frame and carries the legend IVNO POTENS SCEPTRIS ET MENTIS ACVMINE PALLAS / ET ROSEO VENERIS FVLGET IN ORE DECVS / ADFVIT ELIZABETH IVNO PERCVLSA REFVGIT OBSVPVIT PALLAS ERVBVITQ VENVS’. This translates as: ‘Pallas was keen of brain, Juno was queen of might, / The rosy face of Venus was in beauty shining bright, / Elizabeth then came, And, overwhelmed, Queen Juno took flight: / Pallas was silenced: Venus blushed for shame‘.

Baron Waldenstein visited Elizabeth in 1600 and commented on the painting therefore we know that this was in the Royal Collection during Elizabeth’s lifetime. What we are not aware of is whether the painting was a gift from the artist, or from a courtier. Eworth was favoured by Mary I and painted her portrait that was sent to Philip II. Later he was employed by the Office of the Revels right through to his death in 1574. The image (below) attributed to Oliver now in the National Portrait Gallery, is painted on vellum, dated to c1590 and measures 114 x 158mm (4.5 x 6.2 inches), which is considerably smaller than Eworth’s original.

Oliver’s painting clearly shows elements of all three goddesses. Like the Eworth image, Juno has her peacock, Minerva is dressed in armour and the naked Venus is accompanied by her son, Cupid. However, the faces of the women are all very similar, while the earlier and much larger painting resembles earlier portraits of the queen and the faces of the three goddesses and the queen’s attendents all differ. Also in the Oliver painting the queen holds a golden sphere, which is neither an apple nor is it recognisable as the orb. The very distinct addition to the royal paraphenalia is the umbrella, or is it a parasol, held by two of the queen’s three ladies? In the Eworth original there are only two women accompanying the queen and definitely no umbrella/parasol.

The buildings in the background of Oliver’s painting are not recognisable unlike the buildings in the Eworth image. The earlier image that inspired Oliver now hangs in the Queen’s Drawing in Windsor and it is Windsor castle that features in the background of the Eworth painting of c 1569. It is thought to be the earliest representation of Windsor Castle. The unanswered questions are why did Oliver not paint Windsor castle in the background? He was in London so could have taken a trip up the Thames to Windsor. Oliver’s background is more reminiscent of a european walled city on the edge of a river than any landscape in England. We have to ask ourselves for whom did Oliver paint this image (clearly not intended for the queen); was it painted after he had returned from his trip to Italy, hence the foreign looking walled city? He has also included a mountain and Berkshire is not known for its mountains. Perhaps it is an apprentice piece to demonstrate he has reached a certain standard. What is apparent is that Oliver knew the main structure of Eworth’s original painting so was he working from Eworth’s sketches and if so, who had these.

Eworth had died in 1574, but had been a member of the Dutch Church at Austin Friars and a prominent member of the Flemish community. There were a large number of Flemings living in London who had escaped religious persecution in Europe and another of these was the artist Marcus Gheerhaerts. Oliver married Gheerhaert’s sister Sarah in 1602. With such a close knit group of like minded Flemish artists it is possible that Eworth’s sketchbooks had been given to Gheerhaerts or another member of the group. Why did Oliver paint this miniature version of the Eworth original and for whom? Did Hilliard have a hand in challenging his pupil to use Eworth’s image as inspiration for a similar allegorical painting? There were other artists all vying for royal patronage, including Gheerhaerts who also painted the queen. For example, the Ditchley Portrait commissioned by Sir Henry Lee. Hilliard would have known all these artist so it is possible that they all either had access to, or shared, the workbooks from the Eworth workshop. We have no proof and very few of these workshop sketchbooks survive, so this is a guess.

Isaac Oliver’s young man leaning against a tree takes the essence of Hilliard’s Man Amongst Roses to a new level. Oliver’s initials, I O are painted on the rock next to his knee. This link to the Royal Collection will (I hope) allow you to click on it and zoom into the background where you can see the detail of the architecture, the knot garden and the couple walking together. Back in the 18th century, Horace Walpole suggested this was a portrait of Sir Philip Sidney.

Over the years experts have often changed their minds about whether many miniatures portraits were by either Hilliard or by Oliver because at the start of Oliver’s career, their styles were very similar. As Oliver matured he began to develop his own style and after his trip to Italy this becomes very apparent. Andrew Graham Dixon believes that the Rainbow portrait commissioned by Sir Robert Cecil c1600-02, that hangs on the stair at Hatfield House, is by Oliver. Previously it has been attributed to Marcus Gheerhaerts and even Hilliard.

Another portrait, this time of an unknown man that may, nor may not be William Shakespeare, could have been painted either by Hilliard, Isaac Oliver or in my opinion, possibly Marcus Gheerhaerts the Younger.

An analysis of the pigments that could then be compared to the analysis of other paintings by these three artists would go a long way to either confirm or deny the authorship of this portrait. This painting is known as The Wadlow and I discuss whether or not the possibility or otherwise, of it being an advivum portrait of The Bard in my article, Could this be a portrait of William Shakespeare?

Thanks to Hilliard we are able to put the faces to names of many of those courtiers of the court of the Virgin Queen in the same way as his two predecessors, Lucas Horenbout and Hans Holbein the Younger. If Holbein’s surviving sketches were in the Tudor library, then it is possible that Teerlinc showed them to her protégé. Rather than say he had been taught by a woman, when he was drafting his treatise at the end of the 16th century he may have chosen to acknowledge Holbein as his muse having had the privilege of studying his sketches, rather than Teerling, a mere woman. Having a knowledge of the Holbein sketches would go some way to explain why Hilliard believed that painting from life captures the essence of the character of his sitters, which he felt was lost if he worked from sketches.

After James I of England ascended the throne in 1603, the ageing Hilliard continued to create portraits for the royal family and was favoured by the king, but it was Isaac Oliver, his one time apprentice, who was to rise in popularity with the Jacobean court, especially the queen, Anne of Denmark.

Hilliard outlived his talented protégé by two years, Isaac Oliver died in 1617.

Acknowledgements.

My thanks to Rebecca Larrson of www.TudorsDynasty.com who hosted an earlier version of this article; to Dr Paola Ricciardi of the Faculty of Chemistry, Cambridge, for her patience regarding my questions regarding pigment analysis and to Dr Suzannah Lipscomb for her fascinating article on the Ashbourne Charter on her website that has the all images in the charter referred to above. http://suzannahlipscomb.com/2017/09/elizabeth-i-anne-boleyn-and-the-ashbourne-charter-of-1585/

Further Reading & Bibliography.

Fiction: M V Taylor: The Truth of the Line. Revised edition 2018. This novel explores the relationship between Hilliard and Elizabeth I. Was he a spy for Walsingham? Did he record the trial and execution of Mary Queen of Scots? Has he stumbled on a dark royal secret and immortalised this man in the miniature Attici Amoris Ergo? Re-published in 2018 after a substantial re-write of the 2012 original.

Primary Sources:

A very proper way to Limn 1573. Folger Library.

Nicholas Hilliard & Edward Norgate; The Arte of Limning: A More Compendious Discourse Concerning Ye Art of Liming by Nicholas Hilliard; first published in 1834. Carcanet Press and still available.

Secondary sources

Erna Auerbach: Nicholas Hilliard; Routledge, 1961

Erna Auerback: Artists of the Tudor Court, Athlone Press. 1953

Mary Edmund: Hilliard & Oliver: Lives & Works of Two Great Miniaturists: Robert Hale 1983

Karen Hearn; Nicholas Hilliard (English Portrait Miniaturist): Unicorn Publishing Group; 2005

Karen Hearn: Dynasties: Painting in Tudor & Jacobean England 1530-1630: Tate Publishing, 1995

Maurice Howard: Tudor Image: Tate Publishing; 1996

Roy Strong: Artists of the Tudor Court: Portrait Miniature Rediscovered 1520-1620: Victoria & Albert Museum, 1983

Roy Strong; Nicholas Hilliard: Michael Joseph, 1975

a wonderful article

LikeLike

Thank you, Frans.

LikeLike