Our window on to the Henrician court

There is a great deal of historical fiction written – some of it excellent and some of it not so good. If you ask an academic about their opinion of a historical novel it produces a raised eyebrow, often with a sniff and the dismissive response of “it’s fiction!”. A good novelist recognises that history has supplied the basic bare bones of plots, sub plots and the settings so all the author has to do is dress those bones in order to capture the imagination of their readers. To write convincingly requires an in-depth knowledge of the politics, places, houses, costumes, food, entertainment – even the weather. In other words a great deal of research into the surviving documents, the places, the customs and politics is required to create a piece that transports the reader to a specific period. As a result there is a plethora of works set in the 16th century from ‘what if’ novels by those enthusiasts who are fascinated by a specific person such as the many featuring Anne Boleyn, to literary fiction featuring a specific individual. There are also novels written by historians who have spent years studying and have been advised to write their theories about certain events or people as fiction as that research challenges the traditionally accepted history. That way no one can take that theory and claim it as their own – I speak from personal experience!

It is literary fiction written by exceptional authors who write Booker prize winning novels, such as the late Hilary Mantel, that bring new insight into a person or place. Her Wolf Hall trilogy won the Booker twice, and has been dramatized for both television and the stage.

It is through Hans Holbein the Younger’s sketches and portraits that anyone interested in Tudor history recognise members of the Henrician court, and provide casting directors, and set and costume designers the inspiration for these productions. Throughout Mantel’s trilogy we see the world through Sir Thomas Cromwell’s eyes and Hans Holbein (1497 – 1543) is featured in all three books as being an independent artist with close links to Cromwell as opposed to the academic view that he was solely the king’s painter.

Mantel has remained silent about Holbein’s role as an official King’s Painter with an annuity paid at the ‘king’s pleasure’, yet without Holbein’s surviving sketches we would be unable to put faces to the people at the Tudor court described within Mantel’s narrative. Sir Thomas More, the Ladies Mary Shelton, Mary Fitzroy (née Howard) and Margaret Douglas (a possible heir to the English throne and later mother of Lord Darnley), Sir Thomas Wyatt, and many others going by the epithet ‘Anon’ have remained in the Royal Collection since the time of Henry VIII. The likeness of Henry VIII’s friend, Master of Horse and Comptroller of the Royal Household, Sir Henry Guildford and his wife Mary were captured by the German maestro and Guildford’s portrait is held by the Royal Collections Trust (RCIN 40046).

Royal Collection Trust. Oil on Oak Panel. RCIN 400046

Unfortunately, Lady Mary’s ( is now in the United States, but from the preparatory sketch we see how Holbein’s captured Lady Mary’s sense of fun.

In national and international museums and various English country houses we are able to come face to face with original portraits and copies of those of Henry VII, Prince Arthur, and at least four of Henry VIII’s wives. We know from the accounts the king ordered every visual reference of Anne Boleyn erased from the royal palaces and hunting lodges;[i] and Catherine Howard may or may not be the subject of a Holbein portrait miniature held in the Royal Collections Trust.[ii]

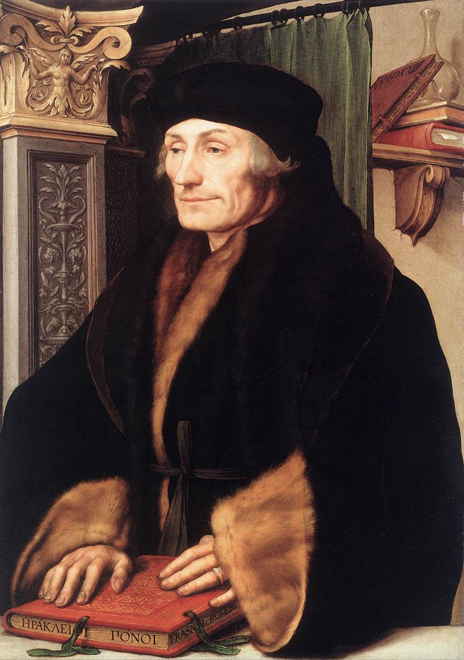

Holbein’s portraits provide a wealth of other information about his sitters. For example that of the Renaissance classical scholar Desiderus Erasmus sent as a gift and as a way of introducing the young artist to Henry VIII’s future Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, Sir Thomas More. Erasmus was a keen on self-promotion and had also been painted by the Hapsburg court painter, Albrecht Dürer, yet the scholar chose to promote the younger artist, and there are many portraits based on the Holbein original. Some may be by Holbein, others with less proveable provenance are attributed to him or described as workshop copies. It is Erasmus’s gift to Sir Thomas More that introduces Holbein’s talents to the English elite, and portraiture as a way of recording a person so they would be remembered through the ages.

In Holbein’s portrait Erasmus sits deep in thought with his hands on a red leather bound book with decorative gold tooling. It is the scholar’s new translation of the New Testament from the original sources, correcting what he saw as the mistakes made through the ages by countless scribes working away in candle lit scriptoria copying ancient texts by hand. The Greek inscription likens his effort to complete this new translation as being as arduous as the labours of the Greek hero, Hercules. Like the reference to Hercules, the Italian Renaissance motifs on the pillar are both a subtle reference to the humanist learning that evolved from the Florentine academy founded by Marsilio Ficino in the 15th century and signifies Erasmus’s humanist scholarship and knowledge of the classics.

A green curtain separates our academic from the rest of the room and is drawn back slightly revealing a shelf with more books. This time a Latin inscription tells us that it is better to mock than to imitate. For those with knowledge of ancient Greek artists may recognise this as a reference to Appeles, court artist to Alexander the Great, who was said to have been the greatest artist in ancient times and is believed to have used a green curtain in his paintings – none of which survive. Holbein’s inclusion of this green drape and the Latin inscription suggests it is a visual a joke shared between him and his sitter. A simple coat of whitewash forms a simple background for our sitter behind that green curtain.

Clad in fur lined robe and a cloth hat Holbein’s sitter’s expression is one of quiet contemplation. His hands rest on his magnum opus and he wears a gold ring set with a diamond on the ring finger of his left hand. Look closer and you see how ink has stained the fingers of his right hand.

Rather than rendering just a photographic likeness of the face, by portraying the books, the ink stained fingers and the décor Holbein has left us clues about the character and passions of this man, as well as providing visual evidence of the decoration of his rooms. The fur lined coat confirms the scholar’s many grumbles about the cold.

Erasmus had also sent Archbishop William Warham (c1450 – 1532) another Holbein portrait of himself and this version is thought to be the one held by the Earl of Radnor. On receipt of that image the elderly archbishop commissioned Holbein to paint a reciprocal portrait of himself to send to Erasmus, but this portrait is now lost. The portrait of the archbishop now in the Louvre, reflects the prelate’s status as Archbishop of Canterbury,

and portrays Warham in a similar pose to that of Erasmus, and like the portrait that inspired this one, we get an insight into what makes this man tick from the inclusion of the various accountrements that were important components of Warham’s life and beliefs. His embroidered archbishop’s mitre and the pre-Reformation primatial cross are prominent.

Warham was the last archbishop before Henry VIII’s ‘Break with Rome’ and when the archbishop died in 1532 the carving on his tomb continues the tradtional Catholic iconography except the cross no longer depicts the crucified Christ. Warham’s tomb can still be seen in Canterbury cathedral where the primatial cross is prominent. This is a photograph of the current Canterbury cross (courtesy of Scott Gunn on Flickr) which is similar in shape to the one seen on the archbishop’s tomb and very different to the one Holbein has depicted in the Louvre portrait. In place of the crucified Saviour is an engraved image of the mother pelican pecking her breast to feed her chicks, a symbol of sacrifice that is derived from the medieval bestiaries.

The two cabochon rubies above and below the crucified Christ on the primation cross seen in Warham’s portrait represent His sacrifice, and the two diamonds on the horizontal arms of the Cross represent constancy because, even in the 16th century, diamonds were known for their hardness as well as value. For those who are wondering why the diamonds are not blazing with reflections, it was traditional to paint diamonds black.

On the mitre are many pearls and diamonds. Pearls have long been a symbol of purity and if you look at the very bottom of this work there is what appears to be a ball of pearls next to the open book. In Van Eyck’s panel portrayal of The Annunciation (National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, USA) there is a similar shaped ball of pearls identifying it as the top of a bookmarker lying between two pages of the book the Virgin has been reading. The similarity of these tiny details suggest that either Holbein was echoing Van Eyck’s painting, or that these bookmarkers were commonly used to mark religious texts – perhaps it is both.

The jacquard woven wallcovering hanging behind the archbishop has a design of five petalled stylistic flowers as part of the weave. The number of petals refer to the five wounds of Christ and the shape of the flower suggests the woven design is based on a dianthus. This species appears in the naturalistic marginalia of many religious texts produced by the many Flemish ateliers in the first part of the sixteenth century. In those contexts the flower represents the nails used in the Crucifixion, which turns our minds turn to Christ’s sacrifice on that first Good Friday. As the foremost prelate of the Church in England it is not surprising that Holbein has included these very subtle religious references within this portrait. However, for the casual modern audience the deeper symbolism will be missed and the items will be considered mere decoration and, for the slightly more perceptive, a statement of wealth.

As for including something decorative, the Turkish rug is more likely an inclusion to convey Warham’s status and the Church’s wealth. Another reason for including a rug with so much red wool is because red is the opposite of green in the colour wheel and the inclusion of a red item adds a certain je ne sais quoi to the portrait. Sixteenth century artists were well aware of what would bring a painting to life, despite colour theory not being an academic subject until the 19th century. One only has to remember the rivalry between J M W Turner and John Constable where the two were exhibiting at a Royal Academy Summer exhibition early in the 1800s and just as the doors were opened to the public Turner added a splash of red pigment to his painting giving it cohesion and totally changing the feel of the painting. One might describe Turner’s addition as the ‘red flick of genius’.

In the early sixteenth century anything red had a more symbolic reference to sacrifice and/or love. Even today dignitaries walk a red carpet at official functions and the more cynical modern minded amongst us might think this would be to hide any blood should there be an assassination attempt on that person’s life; or perhaps it is there as a mark of respect and acknowledgement to those who have dedicated their lives to public duty.

In the preparatory sketches for Warham’s portrait Holbein focuses on capturing Warham’s expression, (Below is RCIN 912272).

Holbein carried out this commission in 1528 when the king was contemplating his lack of a male heir and his eyes had alighted on Mistress Boleyn, so it is no wonder that the archbishop looks glum. Warham had conducted the marriage between Henry VIII and Katharine of Aragon some eighteen previously in 1509 and had served the Crown loyally and successfully as a diplomat and Lord Chancellor during the reigns of Henry VII and Henry VIII before the rise of Thomas Wolsey, to whom he surrendered the role of Lord Chancellor in 1515.

In Holbein’s sketch we get the feeling that the quietly dignified archbishop’s patience was being tested to breaking point. Having chaired the 1531 convocation that declared Henry VIII head of the Anglican church, the next year Warham published an unequivocal protest against the Reformation Parliament that had been summoned in 1529 to settle the king’s Great Matter.[iii]

Archbishop William Warham died on 22nd August 1532 in Canterbury and was succeeded in January 1533 by Thomas Cranmer. The obvious successor to the position was Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester, who had fallen from favour. Cranmer was a reformist and the cleric whose arguments built the legal case that enabled the king to marry Anne Boleyn.

Holbein had been absent from England from 1529 and returned in 1532, and considering his considerable talents it is a wonder that the new archbishop did not commission the German maestro to paint his portrait. It was not until 1545 that Cranmer commissioned another German, Gerlach Flicke, who had come to London and declared himself as the obvious heir to Holbein who had died in November 1543. Examination of Flicke’s portrait shows that Flicke took a great deal from Holbein’s portrait of Archbishop Warham, and may well have known the various portraits of Erasmus.

Like the two previous scholars, Archbishop Cranmer (1489 – 1556) is seated on a chair inlaid with mother of pearl, with a red cushion to spare his poor buttocks from the hard seat. Modern technology has revealed that Flicke has written the German word ‘rot’ meaning red, on the cushion as a reminder to paint it red.

All three men are separated from the viewer by a table on which are placed items that identify their scholarly interests in the Christian faith. In Cranmer’s portrait Flicke has chosen to place his archbishop in front of a glazed window.

When the painting was cleaned the broken panes of glass were revealed and the symbolic meaning of these, and that there were three, has yet to be fully understood. When Edward VI came to the throne Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer was finally published in 1549 so it is possible that Flicke has portrayed three broken panes to suggest that under this archbishop new light has been thrown on to the Word of God. The three broken panes may be a simplistic reference to the Trinity, which was common to both the Anglican and Catholic doctrines. Charlotte Bolland of the National Portrait Gallery has a more nuanced and subtle idea that these broken panes demonstrate the need to repair or completely break down the moral fabric of the Church.[iv]

The curtain is of a fabric woven on a jacquard loom, but the design has no symbolic reference to the five wounds of Christ as seen in Warham’s portrait, the five wounds being very much a Catholic symbol.

The turkey carpet on the table and the Renaissance carved pilaster points to this study being in a palace or at least a place where no expense has been spared in the decoration, therefore, it is unlikely that the three broken panes portray the problems of Tudor glazing. The carved pilaster also echoes that seen in Holbein’s portrait of Erasmus, no doubt Flicke was wishing to show the now encumbent archbishop as a reformer in a similar vein to Erasmus. The religious differences between the two were immense, but both were educated in the humanist manner hence the use of the Renaissance style of decoration on the pilaster in both portraits.

A letter and two books lie on the table. One of them appears to be by St Augustine, a Doctor of the early Church and the archbishop holds a copy of St Paul’s epistles. The viewer gets the feeling that we have disturbed the archbishop’s contemplation of the saint’s letters, but this artist does not have the ability to convey personality in the same capacity as Holbein. Holbein’s two portraits of the eminent scholar and previous archbishop are as if we are looking at the living person. Comparing the portrait of Cranmer to these, Flicke’s boast to being Holbein’s obvious heir falls flat.

Flicke has had the presence of mind to add a ‘cartellino’ attached to the window frame, similar to that seen in Warham’s portrait. In this case it tells us the archbishop’s name and that he is either fifty seven years old or that he is in his fifty seventh year.[v] We have to ask why the artist did this? Was it because he thought that in the future Cranmer’s name would be lost to history? More likely it was as a celebration of the archbishop’s elevation to the head of the new Anglican church, the king’s divorce from Katherine of Aragon having brought about England’s break from Rome, the successful second divorce from Anna, Duchess of Cleves.

Thomas Cranmer had been appointed archbishop in 1533, but Flicke’s portrait was created in circa 1545. The pose, the objects associated with the sitter and the setting is reminiscent of Holbein’s portraits of both Erasmus and Archbishop Warham. Considering Cranmer’s elevation to the position of Archbishop of Canterbury in 1533 it is a mystery why he did not have Holbein paint his portrait that year. He was associated with the Boleyns and was godfather to the Princess Elizabeth, yet he was also involved in the removal of Anne Boleyn in 1536 and later Catherine Howard.[vi] Here we have to enter the realms of speculation. Did Holbein refuse to paint Cranmer? Perhaps he was too busy? Our German maestro had come to England in the 1520s with letters of introduction to Sir Thomas More – a devout Catholic. Amber Gibson’s Master’s thesis examines the differences between More and Cranmer, which could suggest that Holbein had refused to paint Cranmer because he remained loyal to Sir Thomas. Without supporting documentary evidence we shall never know.

In 1532/33 Holbein had no conflicet of interest when Thomas Cromwell took advantage of Holbein’s position as King’s Painter to have his own appointment as Master of the Jewel House immortalised in a portrait. This is now in the Frick Collection, New York and he sits in a similar pose to that of our three remarkable men. Yet Cromwell has not yet reached the apogee of his career. Holbein goes on to paint Cromwell several times over the next few years, repeating the painting now in New York and recording Cromwell’s visage in miniature.

Holbein’s presence in fiction is most apparent in Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall trilogy, and Cromwell’s relationship with Holbein forms an interesting element throughout the three books. When it comes to facts, Holbein and his workshop create two versions of the king’s chief minister seated at a table and clearly contemplating some great matter of state; a further copy was made in the early 17th century.

In addition to that original panel portrait, Cromwell commissioned miniature portraits of himself, first in 1532 (above) and again when he was elevated to Knight of the Garter in 1537. By comparing the earlier miniature to the 1537 one we see how Holbein captures the exigencies of high office in Cromwell’s expression in the later miniature.

Holbein also painted Cromwell’s son Gregory (below) – once when Gregory was a boy and again when he was an adult.[vii]

The adult Gregory was long thought to be a German merchant, but thanks to some incredible investigation work by Teri Fitzgerald, she has identified him as the same sitter once described as “Unknown Boy”. Holbein’s portrait of the young Gregory is in the Royal Collection of the Netherlands, Brussels and the adult portrait (below) now in the Pushkin Museum, Moscow.

You only have to compare the two miniatures to see that this is the same sitter, which means that Holbein painted Gregory three years after his father Thomas was executed, and only months before Holbein’s own death in November 1543.

Teri Fitzgerald has also researched the Unknown Lady in the Toledo Museum, also by Holbein, and her analysis is that this is of Gregory’s wife, Lady Elizabeth, (nee Seymour). Ms Fitzgerald’s research is without doubt, throwing new light on to previously ‘Unknown’ men and women of the Henrician court.

I shall be discussing the contents of the Frick portrait with Dr Owen Emmerson and others at the Wolf Hall Weekend to be held at Cadhay House, Devon at the end of June this year.

MVT

28th March 2024

Footnotes & Further reading.

[i] Royal accounts of September 1536 show that money was paid to workmen to remove any references to both Queen Anne and Cardinal Wolsey from all the royal palaces and hunting lodges.

[ii] Royal Collection Trust 2023/24 exhibition catalogue of Holbein’s work written by Dr Kate Heard, curator.

[iii] https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/evolutionofparliament/originsofparliament/birthofparliament/overview/reformation/#:~:text=Henry%20VIII’s%20Reformation%20Parliament%2C%20which,Papacy%20in%20Rome%20was%20blocking.

[iv] https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw01563

[v] A cartellino is Italian for a small piece of paper, or parchment, painted as if it is attached to a wall, parapet or pillar. It often displays the name of the sitter, and/or artist and the age of the individual, or the year the picture was painted.

[vi] https://www.britannica.com/biography/Thomas-Cranmer-archbishop-of-Canterbury

[vii] Fitzgerald, Teri; MacCulloch, Diarmaid (2016). “Gregory Cromwell: two portrait miniatures by Hans Holbein the Younger”. The Journal of Ecclesiastical History. 67

Sources and Further Reading :

Non-Fiction

Ainsworth, Maryan W. and Joshua P. Waterman with contributions by Timothy B. Husband and Karen E. Thomas, with Dorothy Mahon, Charlotte Hale, George Bisacca, Silvia A. Centeno and Peter Klein (2013); German Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum, New York.

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/German_Paintings_in_The_Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art_1350_1600 This link is to a free downloadable pdf.

Ainsworth, Maryan W. “Early Netherlandish Painting.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000– http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/enet/hd_enet.htm (March 2009)

Fitzgerald, Teri; https://web.archive.org/web/20191006050006/https://queenanneboleyn.com/2019/08/18/all-that-glitters-hans-holbeins-lady-of-the-cromwell-family-by-teri-fitzgerald/

Fitzgerald, Teri; MacCulloch, Diarmaid (2016). “Gregory Cromwell: two portrait miniatures by Hans Holbein the Younger”. The Journal of Ecclesiastical History. 587–601. doi:10.1017/S0022046915003322.(subscription required)

Gibson, Amber: Thomas More, Thomas Cranmer and the King’s Great Matter. Master’s thesis undertaken at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand. https://ourarchive.otago.ac.nz/handle/10523/6524

Heard, Kate; Holbein at the Tudor Court; Exhibition Catalogue; Royal Collections Trust, 2023.

Hearn, Karen (ed); Dynasties: Painting in Tudor and Jacobean England 1530 – 1630; Tate; 1995

Foister, Susan; Holbein in England: Exhibition Catalogue; Tate Britain 2006

Moyle, Franny; The King’s Painter: The Life & Times of Hans Holbein; Apollo; 2021

Wilson, Derek: Holbein the Unknown Man; W&N; 1996

Websites:

Fiction:

Mantel, Hilary; Wolf Hall Trilogy; Fourth Estate; Heruitgave edition (29 April 2021)