So said the late Hilary Mantel in 2013. Unlike a non-fiction examination of a subject Hilary Mantel also believed “A novel should be a book of questions, not a book of answers.” Equally Holbein’s portrait of Thomas Cromwell asks questions that are, only now, beginning to be answered.

Anyone who has tried to write knows that to do so convincingly requires an in-depth knowledge of the politics, places, houses, costumes, food, entertainment – even the weather, in order to create a work that transports the reader to a specific period. Literary fiction brings new insight into a person or place. Mantel’s exploration of the facts, ideas, metaphors, myths and symbols of the Tudor period help create a vivid picture of the Henrician court, with all its political twists and turns that continue to fascinate us.

When it comes to bringing the names of those people in the Wolf Hall trilogy to life, it is through Holbein’s surviving sketches and portraits of the period that provide casting directors and set and costume designers the inspiration for the blockbuster productions we love to watch. It is only through Mantel’s pen we see Holbein featuring in each book. In any film, TV series or documentary he rarely features, even as a bit player, yet it is reported that the king said that he could find many Thomas Cromwell’s, but there was only ONE Holbein!

Hilary Mantel recognised Holbein’s genius and throughout the trilogy he becomes an integral player providing insight into Cromwell’s character adding layers to our own understanding of Cromwell, the man.

The following pages provides an art historian’s analysis of some of the paintings created by this 16th century Apelles[i] whose character and relationship with Thomas Cromwell is so brilliantly brought together by the genius of the late, great, Hilary Mantel.

MVT

June 2024

The court of Henry VIII in the 1520s

In 1526 Holbein arrived in England with letters of introduction and a portrait of Sir Thomas More’s friend, the scholar Desiderus Erasmus of Rotterdam. This image was both a present for Sir Thomas and a way of advertising Holbein’s talent as an artist. Holbein had met Erasmus during his sojourn in Basle where the artist had created works for the publisher, Johannes Fröben, who had published Erasmus’s translation of the New Testament from the original sources.

With work drying up in Basel our artist had set out with high hopes of work in Paris and the French court. No doubt he was keen to find work in the French publishing industry in a similar way as to the various pieces he had produced for Fröben. Unfortunately, Holbein arrived at just the wrong time as the French economy was in a state of collapse.

The court of Francis I and Queen Claude of France was as sophisticated as that of Margaret of Austria, the Hapsburg Regent of the Netherlands. and The French king and queen had been collecting works by Italian artists Fra Bartolomeo, Andrea del Sarto, Pietro Perugino and many others.(ii) In 1519, the great Leonardo da Vinci had died at Chateau Amboise in service to the French king. However, that same year Francis I of France spent 400,000 ecus on his failed attempt to become Holy Roman Emperor and the late emperor’s son, Charles V inherited the position. The following year in 1520 Francis I met Henry VIII of England at the Field of the Cloth of Gold – an unprecedented display of ostentation on both sides. The intent was that they would form an alliance to stand together against the new Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V.

When it came to ostentatious spending it is difficult to put a sheet of paper between Henry VIII and Francis I and just like Henry, Francis was keen to demonstrate his prowess as a warrior. In 1521 hostilities between the young Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V and Francis I commenced and lasted until 1525.

As a warrior king King Francis had started well when his Connétable de France, Charles de Bourbon, had won the battle of Marignano in autumn of 1515, the year Francis had become king. This victory gave Francis overlordship of the territory of Milan. During the ensuing years the relationship between Francis and Bourbon soured and the French army remained unpaid.

By a series of rapid deaths, and a dynastic marriage to Suzanne the daughter and heir of Pierre II, Duc de Bourbon, Charles Bourbon was the wealthiest and next to the king, the most powerful man in France. In order to gain more funds the king instituted proceedings against Bourbon to gain possession of the Duke’s vast lands. Francis’s case was weak and this very obvious attempt to fill the treasury coffers with the result that Bourbon rebelled and joined the emperor’s forces against the French king. In 1524 Queen Claude of France died leaving Louise de Savoie, mother of Francis I, as the most senior woman at the French court and Regent of France during the king’s absence in 1525-26 and 1529. Meanwhile hostilities between the emperor and the French continued.

Francis had inherited Louis XII’s finance minister, Jacques de Beaune, sire of Semblançay, who had the unenviable task of funding the king’s wars. Eventually having squeezed every sou, ecus, livres from any source possible Semblançay made the mistake of raiding the private royal coffers and ended his life stripped of his titles hanging at the end of the hangman’s noose.[iii]

Finally, on 24th February 1525 at the Battle of Pavia Francis I was wounded, captured and taken to Madrid.

Under the terms of the 1526 Treaty of Madrid the widowed French king was betrothed to widowed Eleanora, Charles V’s sister and Francis’s two sons swapped as hostages for the French king to ensure his abiding to all the terms of the treaty. The two boys spent four years in Madrid and it was not until 1529 that the king’s mother, Louise de Savoy, negotiated the Treaty of Cambrai with Margaret of Austria, Regent of the Netherlands that brought an end to the second Italian war between France and the Holy Roman Emperor. The terms were 2,000,000 gold crowns to be given to Emperor Charles V and Francis to give up any claim to the Milanese lands in Italy. In return the Dauphin and his brother were returned.

In short, between 1520 and 1525 Francis had abandoned his allies, lost his best general, emptied the French treasury and bankrupted France.

For Holbein any chance of working Paris, or at the French court was clearly a pipe dream, so armed with the letters of introduction and his portrait of Erasmus he headed for England. Holbein arrived on English shores in the autumn of 1526 no doubt hopeful of finding work as a jobbing artist at the court of Henry VIII and may even had hopes of working with some of the English printers.

He also had letters of introduction to Sir Thomas More and carried one of the most important portraits that exist in the English national collection – that of More’s great friend, Erasmus of Rotterdam. Unfortunately for the English printing industry, it was nowhere near advanced as that of Paris in terms of reputation, but Holbein’s destiny did not lie in that direction.

copyright National Gallery, London. Source Wikipedia

Clad in a fur lined robe and a cloth hat, Erasmus’s expression is one of quiet contemplation. His hands rest on his magnum opus and he wears a gold ring set with a diamond on the ring finger of his left hand. Look closer and you see how ink has stained the fingers of his right hand, while the fur lined coat confirms the scholar’s many grumbles about the cold. His hands rest on the scholar’s translation of the New Testament done from the original sources. The Greek inscription likens his effort in order to complete this work as being as arduous as the labours of the Greek hero Hercules and has the dual element signifying Erasmus’s humanist scholarship and knowledge of the classics. Like the reference to Hercules, the Italian Renaissance motifs on the pillar are a subtle reference to the humanist learning that grew out of the works written by 15th century Italian philosophers such as Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499) and Pico della Mirandolo (1463-1494) and others.

A green curtain separates the revered academic from the rest of the room and is drawn back revealing a shelf with yet more books. This time a Latin inscription tells us that it is better to mock than to imitate. Those with a knowledge of ancient Greek artists may recognise the curtain as a reference to Apelles, court artist to Alexander the Great, who is said to have been the greatest artist in ancient times and is believed to hang a green curtain in front of his paintings (none of which survive). Holbein’s inclusion of this green drape and the Latin inscription further suggests a reference to a private joke shared between Erasmus and Thomas More, or perhaps Holbein himself who was becoming referred to as the 16thcentury embodiment of that ancient Greek artist. A simple coat of whitewashed wall behind that green curtain reflects the more humble working surroundings of this internationally renowned scholar.

In conjunction with his written works this, and the many other portraits of Erasmus, provides us with an intimate knowledge of the character and passions of this man leading us to conclude that our scholar was the first to understand the importance of portraiture as a tool with which to promote himself.

Sir Thomas More was quick to see the advantage of Holbein’s ability to reproduce an accurate and insightful portrait and commissioned one of himself, now in the Frick Collection, New York.

More had been made Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster two years prior to the creation of this portrait. Trained initially as a lawyer, More was the ideal man to be the one to administer the vast estates of the duchy, the income of which provided the personal income of the reigning monarch. More’s eyes look as if he has been burning the candle at both ends and are sore with the strain of looking and concentrating by the light of a guttering flame or two. However, we know he is a rich and wealthy man by the deep rich velvet sleeves, the fur lining to his silk robe, and the gold collar of office.

Erasmus and More were close friends, exchanging letters and from the visual evidence of Holbein’s sketches in the Royal Collection Trust, portraits of each other and the extended More family. Later, and now only known through copies by the late 16th century artist Rowland Lockey, Holbein painted a group portrait of the extended More family. The original painting was destroyed in a fire in the 1700s.

During that first foray to England’s shores Sir Henry Guildford, Henry VIII’s close friend, Master of Horse and Comptroller of the Royal Household, also recognised Holbein’s talents and commissioned a portrait of himself and his second wife Mary (née Wotton). Guildford’s portrait is held by the Royal Collections Trust (RCIN 40046). Like the portrait of More, Guildford is clothed in a rich russet silk and fur lined robe. In his case he wears the collar of a Knight of the Garter and holds his baton of office. He too, like Erasmus and More, is portrayed in front of a drawn back green curtain, and instead of a pillar as in the case of Erasmus, behind Guildford is a fig. This maybe denoting his noble lineage (note to self – further research is required regarding this idea!)

We know from the existing accounts that Guildford employed Holbein to decorate the temporary banqueting house erected to hold the celebrations for the ratification of the 1527 Treaty of Westminster between France & England.

Erasmus’s gift to Sir Thomas More introduces Holbein’s talents to the English elite. In other words, these portraits are all about these great worthies of the Tudor court, and in Guildford’s case about how he now had this fabulous jobbing artist available to use in the decoration of temporary banqueting houses and other areas of royal palaces and hunting lodges.

Holbein had been given permission to leave Basle on the understanding that he would return after five years. During that first sojourn in London, Holbein sketched More’s family and many members of the Henrician court including Thomas Wyatt, Thomas Wriothesley and possibly Anne Boleyn,[iv] but it would be a full ten years before he painted Henry VIII.

In 1529 Holbein left England, returning three years later to find much had happened during the those years of absence. Wolsey was dead and in his place was Thomas Cromwell who in 1532 had only just begun to receive appointments that brought him physically close to the king.

Holbein’s presence in Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall trilogy and Cromwell’s relationship with the artist forms an interesting element throughout the three books. However, Mantel refrains from developing how Holbein’s royal portraiture was used to promote Henry VIII abroad, and mentions as if in passing, how the artist was sent to paint portraits of the various marital candidates whose images were then displayed for Henry VIII’s perusal. Her concentration is on the Cromwell family and household. When it comes to examples of the relationship between Henry VIII’s Mr Fixit and Holbein we have surviving miniature portraits of Cromwell, his son Gregory, and the portrait of Gregory’s wife, Lady Elizabeth (nee Seymour). I have covered these portraits in an earlier post so I won’t repeat myself.

The reader is left to consider that their relationship would have been key to the way royal portraiture becomes established during the artist’s second stay in England. As David Starkey once said in a lecture nearly twenty or so years ago, “Holbein’s portrait of Henry VIII, with his hands on his hips and legs apart, is the first portrait of a fat man!” Holbein solved the problem of how to portray and obese tyrant and has given us the lasting impression of a royal powerhouse – Henry VIII as master of all he surveys!

Cromwell as Master of the Jewel House 1532-33.

As Mantel said, “a novel should be a book of questions, not a book of answers”. The same applies to a portrait and this one poses many questions. Compare this to Holbein’s other portraits and you have to admit the composition is odd.

As we look at the panel there is a vertical piece of wood to the left that may be the architrave of a window through which Cromwell may be looking. His expression suggests he is deep in thought and before him are various items laid on a green cloth, while he holds a folded document in a manner reminescent of Holbein’s portrait of a previous Master of the Jewel House, and Tudor bureacrat, Sir Henry Wyatt (1460-1536). We are left wondering whether it is the content of these documents that Cromwell is considering, or something else.

Behind him, pinned to the wall is jacquard woven fabric. Considering how Holbein was known for including visual elements holding clues to the sitter’s interests or background we can assume this may be a room where the king’s business is conducted and where the king was often present, in which case the walls would be decorated with suitably luxurious woven cloths.

Professor McCulloch’s biography of Cromwell has done much to illuminate details of the early years of Cromwell’s career that have given other historians such a headache. Those ‘missing’ years Cromwell spent with the Florentine Frescobaldi Bank and in the Low Countries are where Cromwell established himself within the european mercantile community. Therefore the inclusion of the wall cloth may also reflect those trading links Cromwell had established within the continental markets while living in Italy and the Low Countries and continued to be so important for English trade.

Knowing that Holbein like to include visual elements that hold clues to his sitter’s interests or background we may assume from the presence of the luxurious fabric wall covering this is a room where the king’s business is conducted and where the king would also be present.

The green cloth on the table respresents a group of men known as The Board of Green Cloth and consisted of the Treasurer of the Household, Comptroller of the Household, the Cofferer and his clerks, all under the authority of the Lord Steward. Their job was to run and audit the accounts of the royal household as well as sitting as a court for offences committed with a twelve mile radius of the royal court, known as ‘the verge’. Strictly speaking, in 1532 Cromwell was not officially a member of this group that met twice a week wherever the monarch was in residence. Thus, this interior scene represents a meeting of the group whose job it was to provide the necessary money for King Henry’s lavish requirements, and that meeting would be anywhere the king was present. Cromwell’s presence indicates that while he was not an official member, his recent appointments to the direct administration of elements of the king’s personal income required his presence. In which case that cloth would be moved to wherever the monarch was in residence, hence Holbein maintaining the ambiguity of the interior.

The only thing was can be sure of is that Thomas Cromwell is seated on a bench in a room with expensive wall hangings. The bench suggests others will be arriving shortly and depending on who they are they may be invited to sit on the bench next to him – especially if they were bringing more papers; or perhaps would have to stand in front of the desk where they may be offered some form of seating we cannot see.

An alternative reading is that the meeting has just concluded and Cromwell is contemplating what has been discussed.

The Frick portrait is now considered to be the original because of the discovery of ‘pentimenti’ in 1985 using Xray. The discovery of ‘pentimenti’ shows where the artist has changed his mind, and establishes any work as the original if there are other versions. Originally a cartellino had been added above Cromwell’s head after Thomas’s execution in July 1540. Prior to this addition, the detail of who this man is written on the top piece of vellum, revealing this is ‘Thomas Cromwell, our well beloved master of the Jewel House‘ (I have put this into modern English). This written detail is understated and added almost as if it were an afterthought. The cartellino can be seen in the workshop copy and the later 17th century version and we have to consider that the decision to include this label was taken by Holbein for the Frick version, and the later version attributed to his workshop, because the writing on the document was very likely to be missed.[v] The Frick panel has suffered from extensive cleaning and the cartellino was removed, but a 1915 photograph shows it still in situ.

Cromwell survived Cardinal Wolsey’s fall in 1529 and his abilities as a lawyer and administrator had not gone unnoticed. Despite his loyalty to the Cardinal that some might have considered a hindrance, Henry VIII saw his value as an administrator and Cromwell became a minor councillor in 1531. What follows is a timeline of Cromwell’s rise to power.

1532

12th April. Archbishop Warham delivered a Commons Supplication against the Ordinaries to the Convocation of Canterbury. The previous Convocation of 1531 had declared Henry VIII as Supreme Head of the Church ‘as far as the law of Christ allows.’[vi]

The same day Henry VIII appointed Thomas Cromwell Master of the Jewel House. An interesting link between Robert Amadas, king’s goldsmith and previous Master of the Jewel House to Cromwell, is that one Antonio Cavallari, an agent of the Frescobaldi bank was listed among Amadas’s debtors,[vii] reminding us that Cromwell’s missing years were spent in Florence with the Frescobaldi bank.

15th May. Convocation surrendered its rights to make provincial ecclesiastical laws independently; that no new canons would be appointed without royal licence and the existing canons would have to submit for revision to a committee appointed by the king.

16th May. Sir Thomas More resigned his position as Lord Chancellor of England in protest.

July. Cromwell appointed Clerk of the Hanaper and together with the position as Master of the Jewel House, Cromwell was now holding official appointments to posts that brought another revenue stream into the private royal coffers (and no doubt his own), and gave him personal access to Henry VIII.

22nd August Archbishop Warham died and is replaced by Thomas Cranmer, who was in Rome at the time.

Despite the king now being the Supreme Head of the Church the King’s Great Matter remains unresolved.

1533

January. Lord Audley appointed Chancellor. Henry VIII secretly marries Anne Boleyn in a ceremony at which Cranmer was not present.

30th March. Cranmer consecrated as Archbishop of Canterbury.

12th April. Cromwell appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer, a position that was yet to become as exalted as it is today.

23rd May. Archbishop Cranmer declares Henry VIII’s twenty four years of marriage to Katharine of Aragon was against the law of God.

28th May. the king’s marriage to Anne Boleyn in the January is validated by Cranmer.

1st June. A visibly pregnant Anne Boleyn anointed as queen of England by Cranmer.

7th September. Queen Anne gives birth to a daughter, Princess Elizabeth. Archbishop Cranmer appointed as a godparent.

Working together Cranmer and Cromwell had brought about the king’s much wanted separation from Katharine of Aragon and given Henry VIII what he wanted. All the while Cromwell was quietly moving towards an evangelical reform of the English church.

§

Thomas Cromwell’s first three relatively minor official positions, gave him direct access to the king’s ear, so it is no wonder that Cromwell commissioned a portrait to celebrate his position as Master of the Jewel House and Clerk of the Hanaper. In the absence of documentary evidence we can only imagine the conversation between the artist and sitter about how Cromwell wished to be portrayed. Of the three appointments he received between 1531 and 1532 it was as master of the Jewel House that was the most important. The Crown Jewels were (and still are) held at The Tower of London, not far from Cromwell’s house at Austin Friars. We should not discount the king’s jackdaw like propensity for obvious display of gold and precious gems that would have required Cromwell to bring a selection of precious geegaws for the king to choose to wear when requested.

In 1532 Holbein was newly returned from his three year absence in Basle to a very changed England. Cardinal Wolsey was dead and despite Cromwell’s loyalty to his former master, he was rising in power with the king. Holbein would have been keen to generate new patrons and Cromwell would have been keen to celebrate his new appointments. In the absence of documentary evidence, we can only imagine the conversation the conversation between the artist and sitter about how Cromwell wished to be portrayed and the various items he wished included. The presence of the letters patent on the table suggests these may have just been received.

However, none of this explains the presence of that book with one corner just over the edge of the table.

The book on the table

The book of hours, discovered in the Wren Library, Cambridge has been researched by Hever curators Alison Palmer, Kate McCaffrey and Owen Emmerson working together with the Trinity College academics and scientists. These historians and scientists have identified it as coming from the French publishing house of the Hardouyn brothers, together with two further copies from the same 1528 edition that were given to Queen Katharine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn.[viii] It is even possible that Queen Anne had her copy with her on the scaffold on 19th May 1536.[ix] Anne Boleyn’s copy, now at Hever Castle Kent, has her words “Remember me when you do prey, that hope doth lead from day to day” that today are barely visible to the naked eye.

Queen Katherine of Aragon’s copy is now owned by the Morgan Library in New York, (Accession No PML1034), and has had the references to St Thomas Becket and the pope scratched out. This may have happened at a later date since the book was passed to the queen’s waiting woman, Margaret Pennington Coke (d1552) and has a clear provenance.[x] This copy was rebound sometime in the 19th century.[xi]

The form of service is Use of Sarum, identifying these books being deliberately created for use in England. The Hardouyn brothers specialised in producing books of hours for the mass market.[xii] Each copy contains hand coloured woodcut illuminations and there is a difference in the quality of those illuminations between the two books owned by the two women with the most influence with Henry VIII. It has been suggested that Henry VIII might have given the two women copies of the same book. Anne’s copy has coloured woodcut illuminations of greater distinctions than the copy given to Queen Katharine.[xiii]

Another suggestion was that Queen Katharine ordered copies and gave one to Anne, but that does not explain why Anne Boleyn had the one with the greater degree of decoration. It is possible both women had heard of the production of a book of hours specifically for use in England and independently requested copies.[xiv]

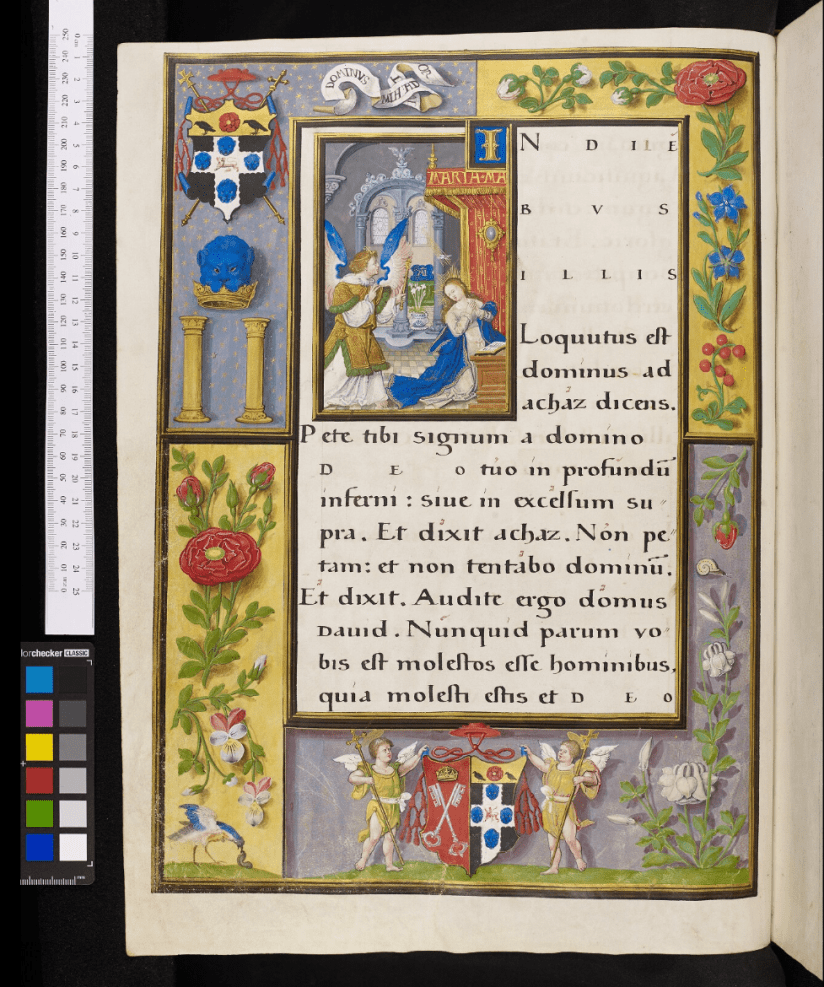

By contrast the copy now in the Wren Library is as if the book has never even been opened. None of the references to St Thomas or the pope have been defaced and there are no markings whatsoever anywhere except within the inside fly leaf that has a hand written entry stating it was given by Anne Sadl[i]er together with a short description in Latin. Pasted on the inside of the front board is a hand coloured woodcut of The Annunciation, which must have been cut out from elsewhere since there is a full page coloured woodcut of the Annunciation on P038 of the Wren library copy (below).

The reason why these three books of hours were sent to England may lie in the parlous state of French finances. Thanks to the iniquitous terms of the 1526 Treaty of Madrid the French economy was in a state of bankruptcy resulting in the collapse of the Parisian book trade. Like every other French publishing house the Hardouyn brothers were looking for new markets.[xv]

The publication date of 1528 and the deliberate Use of Sarum format suggests the Hardouyn brothers were hopeful of being granted letters patent for the importation of copies to be sold to the English public. Why else would copies be sent to the three people they thought were most likely to influence royal patronage – Queen Katharine of Aragon because Henry VIII’s Great Matter was yet to be resolved; Anne Boleyn who was now the obsession of the king and being lined up to be wife number two; and in 1528 Cardinal Wolsey was still in post as the Lord Chancellor and made many of the commercial decisions such as the granting of letters patent.[xvi]

The total absence of any form of rubbing or wear on specific pages, or the defacing of written or visual references to St Thomas Becket or the pope, suggests this book might have been sent to the Cardinal and ended up being swept up in the mass of administrative papers that now form a significant part of Letters & Papers from the first part of Henry VIII’s reign.[xvii] Unfortunately we only have inventories listing the plate owned by the Cardinal, and not a general inventory of his other possessions.

It is unlikely it was a gift because when it came to the level of illuminated books adorning the shelves of Wolsey’s library, we only have to look in the Bodleian library at two manuscripts once owned by the cardinal that demonstrates how Wolsey preferred the expensive traditionally hand crafted manuscript. One is a lectionary of epistles that belongs to Christ Church College, originally founded by the Cardinal and the other a gospel lectionary owned by Magdalen College. Together they are known as the Wolsey Manuscripts. Just who illuminated them has been a matter of much debate.

Comparing the illuminated page with The Annunciation in the illumianted capital letter ‘I’ in the Christ Church college 1528 manuscript to the two wood cut images of The Annunciation in the Wren library copy shows how the cardinal is unlikely to have been impressed by a gift of a mass produced book containing standard woodcut images – albeit hand-coloured.

That the Hardouyn brothers sent copies to the three most influential people around Henry VIII hints the French publishing house was hopeful of being granted letters patent for import this edition to an English mass market.

That Holbein has included the Hardouyn book in his portrait of Cromwell suggests it being an item they discussed, and that Cromwell wanted included.

Since we know Cromwell was already quietly working towards reforming the church in England, the placing of the hours on the edge of the table has to have been a deliberate reference to his evangelical ambitions, which meant sweeping away all elements of what was perceived as idolatrous such as books of hours as well as images, reliquaries, chanceries – the dissolution of the monasteries is well documented elsewhere.

Whether Cromwell’s contemporaries viewing the portrait of the Master of the Jewel House would have known about the existence of the book of hours is another matter. Thanks to the detective work of the Hever curators we know that it came into the Wren Library through the daughter-in-law of Sir Ralph Sadler, Cromwell’s close associate. At the very least Sadler knew of its existence and saved the book when Cromwell was arrested.

That is all very well, but this is all considered from a 21st century viewpoint. To have a more rounded consideration we have to put ourselves in the place of Holbein and Cromwell sometime after April 1532 and Cromwell’s appointment as Master of the Jewel House.

After Wolsey’s fall from grace in 1529, as Cromwell’s influence grew it was necessary for him to acquire a coat of arms and he incorporated many elements of the coat of arms of his late master. (xviii) The presence of Wolsey’s ring on Cromwell’s finger is prominent and would have been a very personal gift. Considering these elements together with the political events that took place between 1528 and 1532 the presence of the Hardouyn book of hours takes on a much more complex and nuanced presence.

The publication date of 1528 suggests that the Cardinal knew of the Hardouyn’s product and ordered copies with the Order of Sarum as gifts for both Queen Katharine and Anne Boleyn, and perhaps others, and dictated the level of illumination in each copy. By presenting both women with these gifts the cardinal was demonstrating his neutrality and perhaps trustworthiness, to bring what has become known as The King’s Great Matter.(xix) In 1528 Cromwell’s duties within the cardinal’s household were growing so it is very possible that Wolsey not only gave copies to the two women whose futures were at stake, but also to his trusted administrator, Cromwell, as a mark of esteem. In which case, the inclusion of the Wren library’s copy of the Hardouyn book of hours becomes a satement of Cromwell’s loyalty towards his late master, to whom Cromwell owed everything.

Holbein enables us to put the faces to so many people who formed the court of Henry VIII’s, but strangely there are no surviving sketches in the Royal Collection Trust of the king’s minister whose reforms changed so much of England’s legislation and whose evangelical ideas were to influence the English Protestant Reformation. Perhaps like the finished portraits of Henry VIII’s executed queens, Holbein’s preparatory sketches of Cromwell were destroyed when the king obtained the artist’s sketches after the maestro’s death in November 1543. Or perhaps they are hidden away in a yet uncatalogued box of documents in an archives waiting to be discovered (wishful thinking on my behalf).

Up until the discovery and identification of the Wren library’s copy of the Hardouyn hours, Ms Mantel had concluded this was a book on the theory of accounting. By taking into consideration the political events of the period the book now becomes a statement of Cromwell’s loyalty to the late cardinal. Equally, thanks to the genius of Holbein, that it sits at the very edge of the table where The Board of Green Cloth meet, its presence hints at Cromwell’s mind set regarding religious reform – or, is it possible to suggest that Holbein has captured the moment that Cromwell has realised that to bring about a resolution of The King’s Great Matter it is going to be necessary for England to break with the Church of Rome? The late cardinal’s mantra was to give Henry VIII what he wanted, and while Wolsey, as a prince of the Church, would never have contemplated such a move, Cromwell had no such restrictions placed upon him.

Sadly Hilary Mantel died before the discovery of this unique and pristine relic of the French printing industry and we can only imagine what she would have made of its discovery.

§

Footnotes.

[i] None of Apelles’s works survive, yet every artist of talent is measured against this artist’s alleged genius. He is documented by Pliny the Elder in his Natural Histories XXXV.79. Pliny dated Apelles as living in the 4th century BC.

[ii] Heard, Kate: Hlbein at the Tudor Court; 8.

[iii] Mullins; unpublished PhD thesis on the French book trade 1501 – 1540; University of St Andrews, 2013. 56

[iv] Heard; Holbein at the Tudor Court; 64-67.

[v] A cartellino is the technical term for a painted label placed within a picture giving information about the sitter such as name, date, and/or position.

[vi] MacCulloch, Diarmaid; Thomas Cromwell; 162.

[vii] Amadas was acting master of the Jewel house from 1524 but only received the sealed letters patent detailing his salary of £50/annum in 1526. Phillipa Glanville; Cardinal Wolsey and the Goldsmiths; Cardinal Wolsey, Church State and Art; (eds S J Gunn & P G Lindley)Cambridge University Press; 1991. 142-143

[viii] For further information on how the Wren library came to own this book of hours, Thomas Cromwell’s Book of Hours in Wren Library and The Hardouyn Hours a jewelled fifteenth century prayerbook that once belonged to Thomas Cromwell Both links are via Trinity College website.

[ix] Lipscomb Channel 5 documentary on Anne Boleyn screened 19th May 2024; McCaffrey 2023.

[x] Morgan Library book of hours once belonging to Queen Katharine of Aragon, Accession No. PML 1034.

[xi] Morgan Library Corsair entry for PMC 1034; McCaffrey 2023.

[xii] Mullins; unpublished PhD thesis on the French book trade. 140-142

[xiii] McCaffrey; A Book Fit for Two Queens; Morgan Library blog. 28/05/21

[xiv] Mullins; 56

[xvi] It was not until a year later on 17th October 1529 that the cardinal was commanded to hand over the Great Seal of England that he had held as Lord Chancellor of England.

[xvii]My thanks to Professor Glen Richardson for taking time to respond to my email regarding inventories of Wolsey’s possession, and to Professor MacCulloch for introducing me to Professor Richardson.

[xviii] MacCulloch 172

[xix] My grateful thanks to Professor MacCulloch for his taking time to discuss this portrait in great depth and reminding me that it is the art historian’s duty to imagine themselves (as far as is possible) in the period they are studying, and take into consideration the political events to provide context to the scene portrayed.

Sources and Further Reading :

Primary Sources:

KB27 series Henry VIII 1509 – 1529 2nd Legal system 1348 – 1529.

KB27 series Henry VIII 3rd Legal system 1529 – 1649.

Letters & Papers, Domestic & Foreign, Henry VIII (via British History Online)

Kings Ms 9 – Another book of hours once owned by Anne Boleyn; British Library.

Pliny the Elder; Natural Histories; Translated by John Bostock, M.D., F.R.S. H.T. Riley, Esq., B.A. London; Taylor and Francis, Red Lion Court, Fleet Street. 1855.

Non-Fiction

Ainsworth, Maryan W. and Joshua P. Waterman with contributions by Timothy B. Husband and Karen E. Thomas, with Dorothy Mahon, Charlotte Hale, George Bisacca, Silvia A. Centeno and Peter Klein (2013); German Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum, New York.

Ainsworth Maryan W. “Early Netherlandish Painting.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/enet/hd_enet.htm March 2009

Auerbach, Erna; Tudor Artists; University of London, The Athlone Press; 1954

Elton, Geoffrey; Tudor Revolution in Government; Cambridge University Press; 1953.

Elton, Geoffrey; The Tudor Constitution; Cambridge University Press; 1982.

Fitzgerald,Teri; All that glitters is not gold 2019. Archived on Wayback Machine in 2023.

Fitzgerald, Teri; McCulloch Diarmaid; “Gregory Cromwell: two portrait miniatures by Hans Holbein the Younger”.The Journal of Ecclesiastical History.587–601.doi:10.1017/S0022046915003322.(subscription required). 2016

Foister, Susan; Holbein in England: Exhibition Catalogue; Tate Britain 2006

Gibson, Amber: Thomas More, Thomas Cranmer and the King’s Great Matter. Master’s thesis undertaken at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand. https://ourarchive.otago.ac.nz/handle/10523/6524 .

Gunn, Steven, & P G Lindley (eds); Cardinal Wolsey: Church, State and Art; Cambridge University Press; 1991

Heard, Kate; Holbein at the Tudor Court; Exhibition Catalogue; Royal Collections Trust, 2023.

Hearn, Karen (ed); Dynasties: Painting in Tudor and Jacobean England 1530 – 1630; Tate; 1995

Knecht, Robert; The Rise & Fall of Renaissance France: 1483 – 1610; Wiley Blackwell; 2001

Kren, Thomas & Scott McKendrik; Illuminating the Renaissance; J P Getty Trust Publications US; 2003

MacKay, Lauren; Among the Wolves of Court; The Untold Story of Thomas and George Boleyn; I. B. Tauris; 2018

MacKay, Lauren; Wolf Hall Companion; The People. The Places. The History; Batsford; 2020

MacCulloch, Diarmaid; Thomas Cranmer; Yale University Press; 1996

MacCulloch Diarmaid; Reformation: Europe’s House Divided; Penguin; 2004

MacCulloch, Diarmaid; Thomas Cromwell: A Life; Penguin; 2019

Moyle, Franny; The King’s Painter: The Life & Times of Hans Holbein; Apollo; 2021

Mullins, Dr Sophie; unpublished PhD thesis Latin Books Published in Paris, 1501 – 1540; University of St Andrews, September 2013.

Wilson, Derek: Holbein the Unknown Man; W&N; 1996

Websites:

Archbishop Warham Canterbury Cathedral; 25/04/2024

https://bestiary.ca/index.html 14/05/2024

Holbein portrait of George Gisz at the Gemäldgalerie Berlin 01/06/2024

Henry VIII’s Reformation Parliament, which, Papacy in Rome was blocking 15/042024

Thomas Cromwell’sBook of Hours in Wren Library accessed via Trinity College website 08/05/2024.

The Hardouin Hours a jewelled fiftheenth century prayerbook that once belonged to Thomas Cromwell accessed via Trinity college website; last accessed 08/05/2024.

https://kateemccaffrey.wordpress.com 05/03/2024

https://history.blog.gov.uk/2013/08/14/the-exchequer-a-chequered-history/ ; 12/05/2024

https://www.duchyoflancaster.co.uk/about-the-duchy/history/ ; 14/05/2024.

https://www.magd.ox.ac.uk/blog/cardinal-wolseys-lectionary/ last accessed 16/05/24

http://aalt.law.uh.edu last accessed 17/05/2

https://www.oxfordreference.com 20/05/24

https://www.themorgan.org/printed-books/111829 20/05/24

https://www.themorgan.org/blog/book-fit-two-queens 21/11/23

Fiction:

Mantel, Hilary; Wolf Hall; Fourth Estate; 2010

Bring Up the Bodies; Fourth Estate; 2013

The Mirror & The Light; Fourth Estate; 2021

Wilson, Derek; The Cromwell Enigma; Marylebone House; 2020